Are Deer Birthing Seasons Changing In The UK?

Share article:

Article by:

Andrea Barden, Marketing & Fundraising Executive, British Deer Society

Guest contribution by:

Dr. Jochen Langbein, LangbeinWildlife

This week the British Deer Society (BDS) is re-launching our UK Deer Birth Dates Survey. The purpose of the survey is to help establish if deer in the UK are giving birth earlier or later in the year than expected.

In our guest blog below, Dr. Jochen Langbein provides some interesting insights on how deer breeding seasons appear to have changed over recent decades, discusses how these changes may be related to climate change, and highlights the need for further research and data to be gathered.

DEER BIRTHING SEASONS IN THE UK – ARE THEY CHANGING?

By Jochen Langbein

CURRENT BIRTHING SEASONS

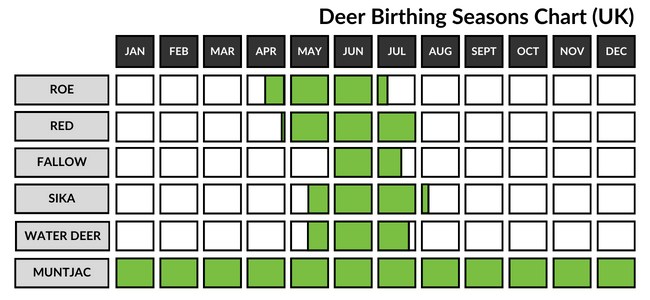

For most of the deer species living wild in the UK, Spring is the time when the first new young of the year tend to appear. The only exception to this is the non-native muntjac (Muntiacus reevesi) that breeds all year round, reflecting their sub-tropical origins. For our native roe and red deer, as well as the introduced fallow, sika and water deer, the month when most of their young are born generally falls within either May or June.

As shown in the chart below, a small proportion of roe kids may already born by late April, but for both roe and red deer the majority of births tend to occur between mid-May to mid-June, or mainly from late May to late June in case of fallow, sika and water deer. This at least has been the conventional wisdom based on observations gathered prior to the start of the new millennium.

GROWING EVIDENCE OF POSSIBLE CHANGES

Over recent years number of reports of deer being born outside of the ranges shown ‘appear’ to be increasing, with not only greater numbers noted to be born earlier on in April and early May, but also more frequent reports of deer calves and fawns born late, in autumn or even early winter.

In case of deer born earlier on in the year, researchers working on the long-term studies of red deer on the Scottish Island of Rum have shown that average parturition date has advanced by nearly 2 weeks over the past 4 decades (Moyes et. al 2011). Furthermore, working on data from that same population Bonnet et. al (2019) have recently provided evidence that genetic evolutionary change underlies that observed advancement of average birthing season in response to climate change.

Interestingly, however, aside from an advancement of average birthing, the number of reports of very late born red deer calves and fallow deer fawns also appears to be increasing. The time spam over which active mating behaviours are being observed, especially for fallow and red deer, also seems to be starting earlier and finishing later especially in southern England. In case of autumn born red deer calves I personally first became more aware of these when seeing several four to six week old calves appear on footage from wildlife cameras I had set up in West Somerset, as shown in this sample video taken during October.

Over the following year several others keen deer watchers I contacted in other parts of the country confirmed that they were finding more wild new-born red deer calves in September and early October, some in north Devon, with others in Shropshire and Staffordshire.

MATING SEASONS MAY BE CHANGING TOO

Detailed observations of a protracted fallow rut that might lead to such late born young have previously been presented by David Dixon (in DEER magazine Winter 2020-21), indicating that between 2007 and 2019 the rut start date advanced on average by approximately 2 weeks and rut end date too was also delayed by a similar amount. To gather more information from around the country on how deer phenology may possibly be changing as a result of climate change, in early 2023 I set up a Facebook group ‘The DeerYear’ where fellow deer watchers are invited to post images and observations of deer always specific just to the current calendar month (which thanks to much support by sharing of posts also to BDS social media has grown to well over 3000 members within a year). During this last winter this too has resulted in several records of very late mating behaviour in fallow in South Devon and Shropshire, and also in case some red deer stags in the Midlands still filmed roaring and mounting hinds not just in January and February, but even into early March (when some other stags were already casting their antlers, which tends to be triggered by the fall in testosterone among males to its lowest of the year!).

While in case of the advancement of average birth times for red deer a link with climate change is evident, the mechanisms leading to a protracted mating season and whether the proportion of deer fawns born as a consequence in autumn is truly increasing is less well understood. As a working hypothesis I would suggest that the progressively milder winters we have experienced over the past two decades, maybe be enabling an overall higher proportion of primiparous female deer (i.e. those conceiving for the first time, usually as yearlings) to reach the required body condition to come into oestrus than in the past as a results of the later onset of winter and end of the grass growing season.

During the late 1980s on the basis of marked fallow deer populations we established in a series of deer parks in southern and northern England, the winter body-weight threshold, at which 50% of yearling produced fawns, was determined as 32 kg (Langbein & Putman, 1992), and yearlings which did reproduce were shown to produce lighter offspring than adults, and to fawn an average of 11 days later. Given generally colder average winter temperatures at that time, maturing free ranging deer would rarely be able to gain more body condition after onset of winter once grass stops growing and loses nutritional value. The annual thermal growing season tends to extend until average temperatures fall below 5.6 °C in winter.

In many recent years however, this has been later throughout the country, but not least in the south of England where average winter temperatures tend in any case to be close to 2 degrees Celsius warmer than in Scotland. Hence, while in colder winters deer would quickly lose condition, in at least parts of the country deer may now continue to gain condition much later into winter in at least some years. This might well be a factor allowing more primiparous females that would in the past have failed to reach adequate body condition for oestrus prior to onset of winter, to continue to gain weight right through November and December, and only then attain sufficient condition for ovulation and conception well into winter; possibly explaining also the increase in reported rutting activity of red and fallow after the end of the year in some parts of England.

Such theorising as to possible underlying reasons is however somewhat premature, within the first instance much more information is required from right across the country in order to establish whether and where earlier and later births are actually occurring; as greater numbers of reports (but not necessarily the proportion) of births occurring earlier as well as later in the year might also arise merely as a result of having higher total numbers of deer in the countryside and hence more reported outliers overall.

In order to help gather more information on how deer are being affected by climate change and in particular how their birth dates may be changing, and how this differs across the UK, the British Deer Society will be continuing their Deer Birth Dates Survey, that was initially started in 2023 for the foreseeable future.

More details about the survey and how you can take part are provided here.

REFERENCES & USEFUL RESOURCES

‘TheDeerYear’ Facebook Group. For anyone who appreciates deer and is keen to contribute to deer photography and research, this is must join community.

Moyes K, Nussey DH, Clements MN, Guinness FE, Morris A, Morris S, et al. Advancing breeding phenology in response to environmental change in a wild red deer population. Glob Chang Biol. 2011;17:2455–2469. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02382.x

Timothée Bonnet, Michael B. Morrissey, Alison Morris, Sean Morris, Tim H. Clutton-Brock, Josephine M. Pemberton and Loeske E. B. Kruuk (2019). The role of selection and evolution in changing parturition date in a red deer population. PLoS Biol. 2019 Nov; 17(11): e3000493. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6830748/

Late autumn born red deer calf video: Langbein Wildlife Youtube. https://youtu.be/dvnc3iwxE60?si=lx4m9oy4No3fwhBq

Dixon, D (2020) The times they are a-changing – new light on the timing of the fallow deer rut. DEER magazine Winter 2020-2021 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349061432_The_times_they_are_a-changing_-_new_light_on_the_timing_of_the_fallow_deer_rut

Langbein, J. and R J Putman (1992) Reproductive Success of Female Fallow Deer in Relation to Age and Condition. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4612-2782-3_64